Digital camera lenses are expensive, so it’s no wonder people are turning to much cheaper second-hand manual focus lenses. However these older, mechanical lenses behave quite differently from the electronic ones that digital camera owners are used to. This article discusses the key differences and will hopefully help you get the best out of manual focus lenses on your digital camera. I will mostly be discussing Canon FD lenses since this is what I know best, but most of the advice applies to any manual focus lens.

Interchangeable lens fundamentals

If you know about SLR interchangeable lens systems, skip this section. Every interchangeable-lens camera, including 35mm SLRs, DSLRs and mirrorless cameras has a lens system, also known as a mount. This is basically a set of lenses designed to work with a set of cameras. For instance, Canon FD lenses work on Canon FD cameras, Canon EF lenses work on Canon EOS cameras and Canon EF-M lenses work on Canon EOS M cameras. Different mounts offer different levels of functionality – the Canon FD mount offers aperture control but no autofocus. EF and EF-M, being designed for autofocus cameras, do offer autofocus.

You can mix things up a bit by using an adapter to mount the “wrong” lens on the “wrong” camera. Depending which lens you put on what camera, you can expect different levels of functionality. Each of the following sections discusses one aspect.

Flange focal distance

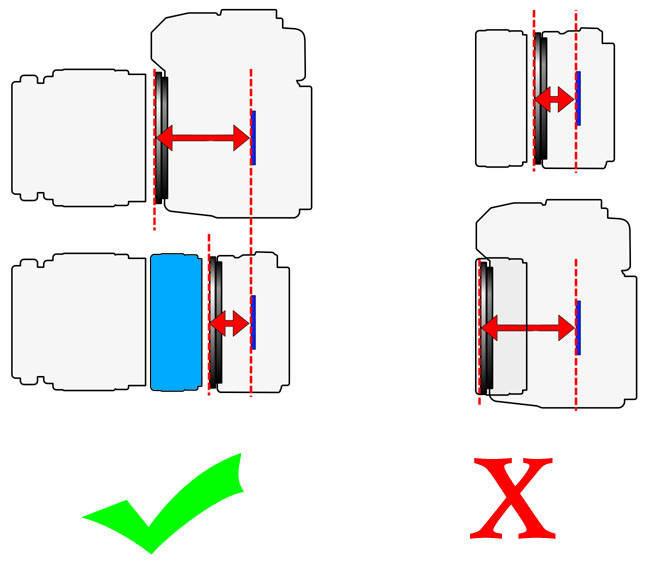

Each mount has something called the flange focal distance. This is the intended distance between the back of the lens, and the sensor (or film). For SLRs, this is usually 40-50mm, so there is enough room for the moving mirror to do its thing. On mirrorless cameras, flange focal distance is usually less than 20mm as there isn’t a mirror.

Adding an adapter between a lens and camera increases the flange focal distance by 5-10mm. If the total distance is longer than the lens’s flange focal distance, that particular camera/lens combo will not be able to focus at infinity. You will not be able to focus more than a few feet away.

For example, the Canon FD mount has a flange focal length of 42mm. The Canon EF mount has a flange focal length of 44mm. Immediately you can see that Canon FD lenses will not focus to infinity on Canon EF/EOS camera – especially not when you add in a 5mm thick adapter. In this case, you’d space the lens out to at least 49mm – which far exceeds 42mm.

Some mount adapters include a lens element of their own which can work around this problem and allow you to focus at infinity even if your total length exceeds the flange focal length of the lens. These are almost never worthwhile, since the glass lens element degrades the image quality. If you are buying an adapter on eBay or similar, look for glassless and infinity focus. Avoid ones that say macro or with optic.

Luckily, mirrorless cameras have such a tiny flange focal length that they can accept pretty much any lens and still focus at infinity using a glassless adapter. This article concentrates on mirrorless cameras, in my case a Canon EOS M, but this also applies to Micro 4/3 cameras like the Sony NEX series, Olympus Pen-E series, some Panasonic Lumix models and other cameras too.

Crop factor

Almost all manual focus lenses were designed for 35mm film cameras which has an image size of 36×24mm. Traditionally this is called the 35mm image format, but these days it is often known as full frame. Most mirrorless cameras have either an APS-C sensor (23×15mm), or a Micro Four-Thirds sensor (18×13.5mm).

The smaller sensor size means the picture will be more “zoomy” for the same focal length. The normal lens is the focal length that gives a standard field of view with a specific camera. For 35mm full frame cameras, the normal lens is 50mm (and that’s what was bundled with every 35mm SLR as a kit lens). For mirrorless cameras, the normal lens has a shorter focal length. If you want a lens with a normal field of view, you’ll need a shorter focal length than 50mm. However you’ll also find that 50mm is a nice focal length for portraits on mirrorless cameras.

The crop factor tells you how more “zoomy” the lens is on your mirrorless camera than on its original 35mm SLR. Don’t worry too much about the crop factor; it doesn’t mean a huge amount and yet some people put a lot of emphasis on it.

| Sensor type | Size | Normal lens | Crop factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35mm full frame | 36×24mm | 50mm | 1.0× |

| APS-C | 23×15mm | 35mm | 1.5× |

| Micro 4/3 | 18×13.5mm | 24mm | 2.0× |

Manual focus

As this article is about manual focus lenses, hopefully by now you’ve realised you don’t get autofocus! Manual focus isn’t hard, but cameras originally designed for manual focus (like Canon FD SLRs) have focusing aids like microprisms or a split image circle. Autofocus cameras don’t have these things, so you should use live view and focus as carefully as possible. You can also use the magnified live view for precise focusing.

Metering

In most cases, automatic metering relies on the camera knowing what the lens aperture is set to, and what the lens’s maximum aperture is. In digital lenses this is done with digital electrical contacts around the edge of the lens mount and in manual focus lenses this is usually done with a set of mechanical linkages.

Lens adapters do not convert one kind to the other, so your camera will be flying blind. The only way to get accurate auto-exposure on a mirrorless camera with a manual focus lens is to use aperture priority metering, also known as A or Av mode. The idea behind A mode is the photographer sets the aperture and the camera chooses the correct shutter speed for the right exposure. Even if the camera can’t tell what your aperture dial is set to, it will choose the best shutter speed for whatever amount of light is entering the camera.

Canon FD lenses are what was known as “automatic” in the 1970s. This means whatever you set the aperture ring to, the aperture diaphragm doesn’t actually change until it receives a signal from the camera (by prodding a lever) and it temporarily stops down the aperture at the moment the photo is taken. This means the aperture stays wide open while you are focusing, so the viewfinder is nice and bright.

A digital mirrorless camera can’t send the stop-down signal, so Canon FD lens adapters have a switch which can be set to A or M (on some adapters they are marked OPEN/CLOSED, OPEN/LOCK or even OFF/ON). Set the adapter to A or OPEN while focusing and switch it to M or CLOSED to stop down the aperture to the chosen value when you take the picture. Many mirrorless cameras have a live view that is sensitive enough that you can keep the aperture stopped down all the time.

Summary

- Use a digital mirrorless camera rather than an SLR – you’ll have many more options

- Avoid lens adapters with glass optics

- Remember manual focus lenses have a narrower field of view on mirrorless cameras

- Use magnified live view for precise focusing

- Focus with the aperture open, and then stop it down for taking the picture

I hope I’ve covered everything. If not, please ask in the comments!