Recording a choir and organ in a church is one of the hardest things a recording engineer can do. There are loads of guides on the internet that explain how to use which type of microphone to use and where to put it, but most of these guides fail to give clear advice on recording in a church. It’s not the fault of the guides; the sound in a church depends on the size and layout of the church, where the choir are and where the organ is just as much (if not more) than the quality of the sound itself. There are just too many variables to be able to give concrete recommendations.

I’ve been recording the choir at St Mary’s, Fishponds for several years now and I’ve been making incremental improvements all the time. From the beginning, I owned a pair of small-diaphragm condenser (SDC) microphones with cardioid pickup pattern – Behringer C-2.

At the beginning I used these cardioid SDCs in the tried-and-tested XY pattern – also known as coincident pair. You mount the microphones pointing inwards at 90° to each other, with the tips touching. The results were OK. The consonants were sharp but there was not much reverb and the organ (which is at the far end of the building) didn’t sound great.

Later I experimented with these cardioid microphones arranged in an ORTF pattern – also known as near-coincident. The microphones are mounted pointing away from each other at about 100° and with the tips about 17cm apart. I wrote about ORTF at the time and I preferred the results to XY.

More recently, I got my hands on a pair of SDC microphones with omnidirectional pickup pattern – Behringer B-5. The norm for stereo recording with omnidirectional microphones is to use the microphones facing the same direction but spaced a few feet apart – a so-called “spaced pair” or an AB pattern. The spacing depends on the building and the “size” of the sound source (solo artist vs choir).

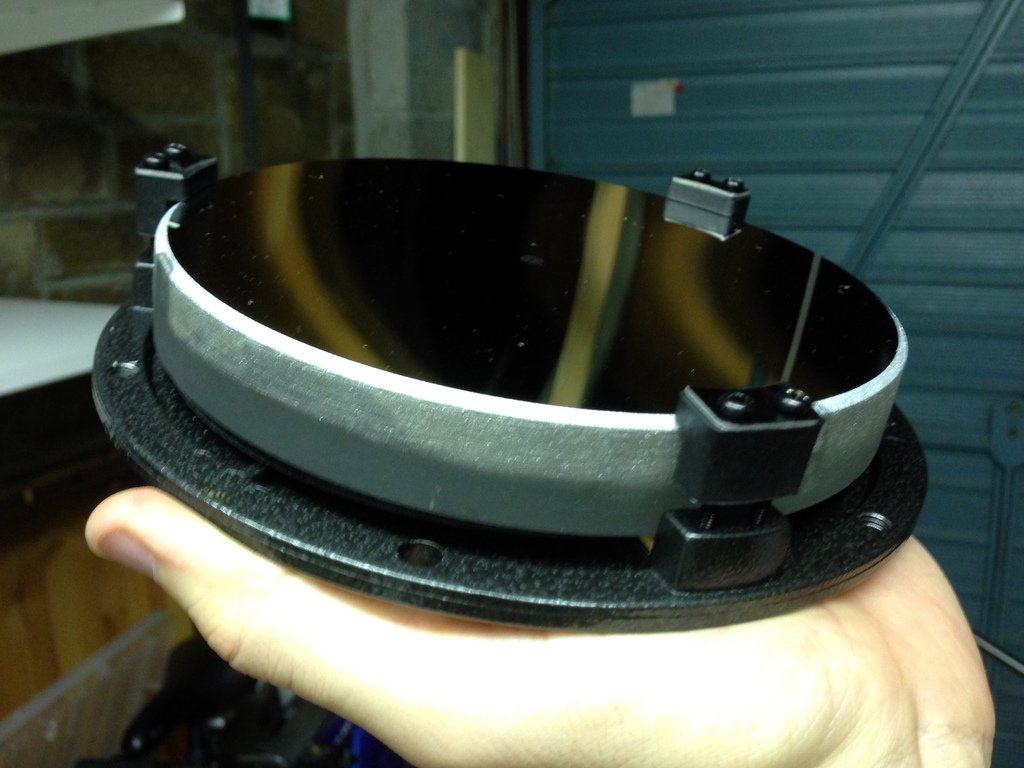

As with any new microphone, it can’t be trusted until it has been tested – so I recorded a service this week using the XY and AB methods simultaneously. This picture shows the setup. The microphone stand in the middle is holding the pair of XY cardioid microphones while the two stands flanking it, near the pillars, are holding the spaced pair of AB omnidirectional microphones.

To give you some context of the size and shape of the church, here’s a drawing I made. All dimensions are in metres. The two grey blocks near the top of the drawing are the choir stalls. The rectangle with diagonal corners cut off is the step that’s visible in the photo above, and that’s where I put the microphones. To make matters more complicated, the organ pipes are above the door at the very back of the church (bottom of the drawing).

I much prefer the AB placement and so do a couple of people who have heard the recording. But it’s up to you to decide! I’ve included two clips: the first is a short section of Sanders‘ responses, to illustrate the sound of an unaccompanied choir. The other is the tail end of the Gloria from Stanford’s Evening Service in C, to illustrate the sound of the organ.

Sanders responses – AB

Sanders responses – XY

Stanford in C – AB

Stanford in C – XY

Personally, I find that the AB recordings sound smoother and mellower, provide a better stereo image, a more realistic balance between choir and organ, and a nice ambience of the room. Of course that’s just my opinion based on one test recording, so your mileage may vary. This Sunday it’s Advent Carols at St Mary’s and I will be recording again. I plan to use only the AB microphone placement and I think I will place the microphones slightly closer together.

I hope these notes will be of use to someone who is thinking of recording in a church 🙂